Low Countries Theatre Of The War Of The First Coalition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Low Countries theatre of the War of the First Coalition, in British historiography better known as the Flanders campaign, was a series of campaigns in the

On 6 November 1792, French commander

On 6 November 1792, French commander

The execution of the deposed French king

The execution of the deposed French king

At the beginning of April the Allied powers met in conference at Antwerp to agree their strategy against France. Coburg was a reluctant leader and had hoped to end the war through diplomacy with Dumouriez, he even issued a proclamation declaring he was the "ally of all friends of order, abjuring all projects of conquest in the Emperors name", which he was immediately forced to recant by his political masters. The British desired

At the beginning of April the Allied powers met in conference at Antwerp to agree their strategy against France. Coburg was a reluctant leader and had hoped to end the war through diplomacy with Dumouriez, he even issued a proclamation declaring he was the "ally of all friends of order, abjuring all projects of conquest in the Emperors name", which he was immediately forced to recant by his political masters. The British desired

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

conducted from 20 April 1792 to 7 June 1795 during the first years of the War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the Kingdom of France (1791-92), constitutional Kingdom of France and then t ...

. As the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

radicalised, the revolutionary National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

and its predecessors broke the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

's power (1790), abolished the monarchy (1792) and even executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

the deposed king Louis XVI of France

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was e ...

(1793), vying to spread the Revolution beyond the new French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

's borders, by violent means if necessary. The First Coalition, an alliance of reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

states representing the Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

in Central and Western Europe – Habsburg Austria (including the Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the A ...

), Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

(the Northern Netherlands), Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

and Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, was a state in the Holy Roman Empire that was directly subject to the Emperor. The state was created in 1567 when the Lan ...

– mobilised military forces along all the French frontiers, threatening to invade Revolutionary France and violently restore the monarchy. The subsequent combat operations along the French borders with the Low Countries and Germany became the primary theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

of the War of the First Coalition until March 1796, when Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

took over French command on the Italian front.

The April–June 1792 French incursions into the Austrian Netherlands were a disaster, eventually leading frustrated radical revolutionaries to depose the king in August. An unexpected French success in the Battle of Jemappes in November 1792 was followed by a major Coalition victory at Neerwinden in March 1793. After this initial stage, the largest of these forces assembled on the Franco-Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

border. In this theatre a combined army of Anglo-Hanoverian, Dutch, Hessian, Imperial Austrian and (south of the river Sambre

The Sambre (; nl, Samber, ) is a river in northern France and in Wallonia, Belgium. It is a left-bank tributary of the Meuse, which it joins in the Wallonian capital Namur.

The source of the Sambre is near Le Nouvion-en-Thiérache, in the Aisne ...

) Prussian troops faced the republican Armée du Nord

The Army of the North or Armée du Nord is a name given to several historical units of the French Army. The first was one of the French Revolutionary Armies that fought with distinction against the First Coalition from 1792 to 1795. Others existe ...

, and (further to the south) two smaller forces, the Armée des Ardennes

The Army of the Ardennes (''armée des Ardennes'') was a French Revolutionary Army formed on the first of October 1792 by splitting off the right wing of the Army of the North, commanded from July to August that year by La Fayette. From July to ...

and the Armée de la Moselle

The Army of the Moselle (''Armée de la Moselle'') was a French Revolutionary Army from 1791 through 1795. It was first known as the ''Army of the Centre'' and it fought at Valmy. In October 1792 it was renamed and subsequently fought at Trier, F ...

. The Allies enjoyed several early victories, but were unable to advance beyond the French border fortresses. Coalition forces were eventually forced to withdraw by a series of French counter-offensives, and the May 1794 Austrian decision to redeploy any troops in Poland.

The Allies established a new front in the south of the Netherlands and Germany, but with failing supplies and the Prussians pulling out, they were forced to continue their retreat through the arduous winter of 1794/5. The Austrians pulled back to the lower Rhine and the British to Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

from where they were eventually evacuated. The victorious French were aided in their conquest by Patriots from the Northern and Southern Netherlands, who had previously been forced to flee to France after their own revolutions in the north in 1787 and in the south in 1789/91 had failed. These Patriots now returned under French banners as "Batavians

The Batavi were an ancient Germanic tribe that lived around the modern Dutch Rhine delta in the area that the Romans called Batavia, from the second half of the first century BC to the third century AD. The name is also applied to several milit ...

" and "Belgians

Belgians ( nl, Belgen; french: Belges; german: Belgier) are people identified with the Kingdom of Belgium, a federal state in Western Europe. As Belgium is a multinational state, this connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultur ...

" to 'liberate' their countries. The republican armies pushed on to Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

and early in 1795 replaced the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

with a client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

, the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic ( nl, Bataafse Republiek; french: République Batave) was the successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 and ended on 5 June 1806, with the accession of Louis Bona ...

, whilst the Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The p ...

and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège

The Prince-Bishopric of Liège or Principality of Liège was an Hochstift, ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that was situated for the most part in present-day Belgium. It was an Imperial State, Imperial Estate, so the List of ...

were annexed by the French Republic.

Prussia and Hesse-Kassel would recognise the French victory and territorial gains with the Peace of Basel

The Peace of Basel of 1795 consists of three peace treaties involving France during the French Revolution (represented by François de Barthélemy).

*The first was with Prussia (represented by Karl August von Hardenberg) on 5 April;

*The sec ...

(1795). Austria would not acknowledge the loss of the Southern Netherlands until the 1797 Treaty of Leoben

The Peace of Leoben was a general armistice and preliminary peace agreement between the Holy Roman Empire and the First French Republic that ended the War of the First Coalition. It was signed at Eggenwaldsches Gartenhaus, near Leoben, on 18 Apr ...

and later the Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The treat ...

. The Dutch stadtholder

In the Low Countries, ''stadtholder'' ( nl, stadhouder ) was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The ''stadtholder'' was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and H ...

William V, Prince of Orange

William V (Willem Batavus; 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806) was a prince of Orange and the last stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. He went into exile to London in 1795. He was furthermore ruler of the Principality of Orange-Nassau until his death in ...

, who had fled to England, also initially refused to recognise the Batavian Republic, and in the Kew Letters

The Kew Letters (also known as the Circular Note of Kew) were a number of letters, written by stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange between 30 January and 8 February 1795 from the "Dutch House" at Kew Palace, where he temporarily stayed after hi ...

ordered all Dutch colonies to temporarily accept British authority instead. Not until the 1801 Oranienstein Letters

The Oranienstein Letters are a series of letters sent by William V, Prince of Orange in December 1801 from Schloss Oranienstein near Diez, Germany. William addressed them to 15 Orangist ex-regenten of the old Dutch Republic and advised them end th ...

would he recognise the Batavian Republic, and his son William Frederick accept the Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda as compensation for the loss of the hereditary stadtholderate.

Background

France, Britain and the Dutch Republic

By the end of theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

the early 1780s, France was providing significant financial support to the American rebels to help the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

break away from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. Although London had to recognise the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

' independence in 1783, this French foreign policy success came at a terrible financial cost, as the Bourbon kingdom struggled with enormous debts. The Eden Agreement of 1786 ended the Anglo-French economic war and allowed both countries to somewhat recover, but the terms were very unfavourable to the French, stoking resentment.

The Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

had been divided on the American Revolution; whilst the stadtholderian regime of William V, Prince of Orange

William V (Willem Batavus; 8 March 1748 – 9 April 1806) was a prince of Orange and the last stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. He went into exile to London in 1795. He was furthermore ruler of the Principality of Orange-Nassau until his death in ...

sought to back his cousin George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

of Britain against the American rebels, a large group of democratic-republican Dutch Patriot ''regenten

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the regenten (the Dutch plural for ''regent'') were the rulers of the Dutch Republic, the leaders of the Dutch cities or the heads of organisations (e.g. "regent of an orphanage"). Though not formally a hered ...

'' supported the rebels and sought to trade with them. Rising tensions led to Britain declaring the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War ( nl, Vierde Engels-Nederlandse Oorlog; 1780–1784) was a conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. The war, contemporary with the War of American Independence (1775-1783), broke out ove ...

(1780–1784), which thoroughly decimated the Dutch navy. The land defences of the Northern Netherlands were also in poor condition, its States Army not having fought in a war for 45 years. Growing Patriot dissatisfaction with the Orangist government during the war prompted the so-called Batavian Revolution, spurred on by the 1781 pamphlet ''Aan het Volk van Nederland

''Aan het Volk van Nederland'' (; English: ''To the People of the Netherlands'') was a pamphlet distributed by window-covered carriages across all major cities of the Dutch Republic in the night of 25 to 26 September 1781. It claimed the entire ...

'' (spread anonymously by Joan Derk van der Capellen), which called on all citizens to arm themselves and overthrow the stadtholder. Tensions between the two factions escalated to a brief, low-level civil war in 1786–1787.

William V only managed to suppress the Patriot revolt with great difficulty after the Prussian and British intervention in 1787, exiling many Patriots to France. William's Anglo-Prussian allies enabled him to preserve the House of Orange

The House of Orange-Nassau (Dutch language, Dutch: ''Huis van Oranje-Nassau'', ) is the current dynasty, reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the Politics and governm ...

, and strengthen his authoritarian stadtholderate regime by the Act of Guarantee

The Act of Guarantee (Dutch: ''Akte van Garantie'') of the hereditary stadtholderate was a document from 1788, in which the seven provinces of the States General and the representative of Drenthe declared, amongst other things, that the admiralty ...

(April 1788). Under the August 1788 Triple Alliance, the United Provinces became a ''de facto'' Anglo-Prussian protectorate. When the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

broke out in May–June 1789, Britain and the Dutch Republic initially adopted a neutral policy towards the revolution in France, which temporarily withdrew from the international stage to deal with internal problems. Even when Southern Netherlandish revolutionaries offered William to unite the Low Countries under his house in May 1789 and early 1790, the Northern stadtholder rejected the advances and refused to get involved.

Southern Netherlands, Austria and Prussia

While the French Revolution unfolded, simultaneous political crises were brewing in the Austrian Netherlands, asemperor Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

had been seeking to force through various political reforms since 1787, in the face of opposition from the conservative nobility and clergy. Revolutionary Henri Van der Noot

Henri van der Noot, in Dutch Henrik van der Noot, and popularly called Heintje van der Noot or Vader Heintje (7 January 1731 – 12 January 1827), was a jurist, lawyer and politician from Brabant. He was one of the main figures of the Brabant Revo ...

had vainly lobbied at the Orangist and British courts in May 1789 for a military intervention in the Southern Netherlands to drive out the Habsburg Austrians. Only Prussia showed limited interest in his request; it rejected revolutionary ideas, but found any chance to weaken its Habsburg rival attractive. Matters came to a head when Joseph II launched a coup d'état on 18 June 1789, unilaterally abolishing the States-General and revoking all noble privileges. Archbishop Joannes-Henricus de Franckenberg eventually called for armed resistance to defend the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and the secret society ''Pro aris et focis

''Pro aris et focis'' ("for hearth and home") and ''Pro Deo et patria'' ("for God and country") are two Latin phrases used as the motto of many families, military regiments and educational institutions. ''Pro aris et focis'' literally translates " ...

'' of Jan Frans Vonck

Johannes Franciscus Vonck, also known by the Francization Jean-François Vonck or the Netherlandization Jan-Frans Vonck, (29 November 1743 – 1 December 1792) was a lawyer and one of the leaders of the Brabant Revolution from 1789–1790. This R ...

and Jan-Baptist Verlooy

Jan-Baptist Chrysostomus Verlooy ( Houtvenne, 22 December 1746 - Brussels, 4 May 1797) was a Brabantian jurist and politician from the Southern Netherlands.

Childhood and descent

Verlooy belonged to a family of local notables who owned extensive ...

began recruiting troops for a rebel army. Some exiled Northern Patriots living in Brussels joined. With the French Revolution to the south escalating, and the Liège Revolution

The Liège Revolution, sometimes known as the Happy Revolution (french: Heureuse Révolution; wa, Binamêye revolucion), against the reigning prince-bishop of Liège, started on 18 August 1789 and lasted until the destruction of the Republic ...

erupting in the neighbouring Prince-Bishopric of Liège

The Prince-Bishopric of Liège or Principality of Liège was an Hochstift, ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that was situated for the most part in present-day Belgium. It was an Imperial State, Imperial Estate, so the List of ...

in August 1789, the Brabant Revolution

The Brabant Revolution or Brabantine Revolution (french: Révolution brabançonne, nl, Brabantse Omwenteling), sometimes referred to as the Belgian Revolution of 1789–1790 in older writing, was an armed insurrection that occurred in the Aust ...

finally broke out in the Austrian Netherlands in October 1789. The Brabantine rebel army defeated the Austrian forces at the Battle of Turnhout in October, and by January 1790, revolutionary Patriots led by Van der Noot and Vonck had taken control of most of the Southern Netherlands, and proclaimed the United Belgian States

The United Belgian States ( nl, Verenigde Nederlandse Staten or '; french: États-Belgiques-Unis; lat, Foederatum Belgium), also known as the United States of Belgium, was a short-lived confederal republic in the Southern Netherlands (modern-da ...

, alongside the Liège Republic. Both rebel states were unofficially protected by a Prussian army occupying Liège to thwart possible Austrian attempts at restoration.

However, aside from the small Prussian force, no foreign power supported the young Belgian polity. And although many revolutionaries in Brussels wore orange cockade

A cockade is a knot of ribbons, or other circular- or oval-shaped symbol of distinctive colours which is usually worn on a hat or cap.

Eighteenth century

In the 18th and 19th centuries, coloured cockades were used in Europe to show the allegia ...

sin January and February 1790, in hopes of uniting the Northern and Southern Netherlands under the House of Orange, William V once again showed no interest. Moreover, divisions within the Brabantine rebellion soon led to conflict between the conservative Statists led by Van der Noot and the liberal Vonckists

The Vonckists ( nl, Vonckisten) were a political faction during the Brabant Revolution led by Jan Frans Vonck, opposed to the more conservative " Statists".

History

The group emerged from the secret society ''Pro aris et focis'' in the 1780s, and ...

, who were expelled. Finally, after Joseph II died and was succeeded by his brother Leopold II, he reconciled himself with Frederick William II of Prussia

Frederick William II (german: Friedrich Wilhelm II.; 25 September 1744 – 16 November 1797) was King of Prussia from 1786 until his death in 1797. He was in personal union the Prince-elector of Brandenburg and (via the Orange-Nassau inherita ...

with the Treaty of Reichenbach (27 July 1790), as they both feared French aggression and decided to cooperate. Due to Anglo-Austrian diplomatic pressure, Prussian troops were withdrawn from Liège to allow an Austrian restoration. Vienna's truce with the Ottomans in September freed up 30,000 troops for an expedition to the Southern Netherlands, ending both the United Belgian States and the Liège Republic by January 1791. Most Statists would reconcile themselves with Leopold II's conservative government. Revolutionary fervour had not perished, however, and when French Republican forces invaded the South in November 1792, Liégeois and Vonckist Patriots would aid in their conquest. About 2,500 Liégeois and Southern Netherlandish emigrants fought on the French side in the Battle of Jemappes.

Ernst Kossmann (1986) analysed: 'In the end, the whole conflict in North and South had the same conclusion: the Prussian army met just as little resistance in the utchRepublic as the Austrian did in Belgium. And just like the restored Orangist regime turned the Patriots into Francophile extremists, the Vonckists exiled to France forgot the nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

out of which their movement had emerged, and eventually they would gleefully welcome the foreign revolution into their country. The major fact of subsequent years is the denationalisation of the democratic reform faction that had originated from nationalism.'

Outbreak of war

Meanwhile, the failed June 1791 Flight to Varennes of kingLouis XVI of France

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was e ...

and his Austrian-born queen Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

(Leopold II's sister) sparked more anti-royalist and republican sentiment, radicalising the French Revolution further. With their differences settled and the Brabant and Liège Revolutions in the Southern Netherlands crushed, Austria and Prussia turned their attention to France, issuing the Declaration of Pillnitz

The Declaration of Pillnitz was a statement of five sentences issued on 27 August 1791 at Pillnitz Castle near Dresden (Saxony) by Frederick William II of Prussia and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II who was Marie Antoinette's broth ...

(27 August 1791) that it was "in the common interest of all sovereigns of Europe" that no harm may come to the French royal family, and that if necessary, they would militarily intervene in order to protect the monarchy. The Girondins

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnard ...

, the dominant faction in the Legislative Assembly, sought to export the revolution abroad and also break the power of other European monarchs, while Louis XVI hoped that his full royal powers would be restored if France lost a war with Austria and Prussia, which had concluded a defensive alliance on 7 February 1792. Thus, supported by the Girondin Assembly, king Louis XVI of France declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792; Prussia immediately joined its Austrian ally against France. Britain and the Northern Netherlands sought to maintain their neutrality, but the British government was increasingly concerned about the security of the United Provinces.

Overall Allied command was led by the Austrian commander Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Prince Frederick Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (german: Friedrich Josias von Sachsen-Coburg-Saalfeld) (26 December 1737 – 26 February 1815) was an Austrian nobleman and military general.

Biography

Born at Schloß Ehrenburg in Coburg, he wa ...

, with a staff of Austrian advisers answering to Emperor Francis II

Francis II (german: Franz II.; 12 February 1768 – 2 March 1835) was the last Holy Roman Emperor (from 1792 to 1806) and the founder and Emperor of the Austrian Empire, from 1804 to 1835. He assumed the title of Emperor of Austria in response ...

and the Austrian Foreign Minister Johann, Baron Thugut. When Britain entered the war in February 1793, the Duke of York was obliged to follow objectives set by Pitt's Foreign Minister Henry Dundas

Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, PC, FRSE (28 April 1742 – 28 May 1811), styled as Lord Melville from 1802, was the trusted lieutenant of British Prime Minister William Pitt and the most powerful politician in Scotland in the late 18t ...

. Thus Allied military decisions in the campaign were tempered by political objectives from Vienna and London.

Opposing the Allies, the armies of the French Republic were in a state of disruption; old soldiers of the Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

fought side by side with raw volunteers, urged on by revolutionary fervour from the représentant en mission

During the French Revolution, a ''représentant en mission'' (; English: representative on mission) was an extraordinary envoy of the Legislative Assembly (1791–92) and its successor the National Convention (1792–95). The term is most ofte ...

. Many of the old officer class had emigrated, leaving the cavalry in particular in chaotic condition. Only the artillery arm, less affected by emigration, had survived intact. The problems would become even more acute following the introduction of mass conscription, the Levée en Masse

''Levée en masse'' ( or, in English, "mass levy") is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period followi ...

, in 1793. French commanders balanced between maintaining the security of the frontier, and clamours for victory (which would protect the regime in Paris) on the one hand, and the desperate condition of the army on the other, while they themselves were constantly under suspicion from the representatives. The price of failure or disloyalty was the guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at th ...

.

1792 campaign

Initial French disasters

The first skirmishes on the northern front took place during the battles of Quiévrain andMarquain

Marquain ({{IPA-fr, maʁkɛ̃) is a village of Wallonia and a district of the municipality of Tournai, located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is ...

(28–30 April 1792), in which ill-prepared French revolutionary armies were easily expelled from the Austrian Netherlands. The revolutionaries were forced on the defensive for months, losing Verdun and barely saving Thionville until the Coalition's unexpected defeat at Valmy (20 September 1792) turned the tables, and opened up a new opportunity for a northward invasion. The fresh momentum emboldened the revolutionaries to definitively abolish the monarchy and proclaim the French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

the very next day.

Battle of Jemappes and Austrian retreat

On 6 November 1792, French commander

On 6 November 1792, French commander Charles François Dumouriez

Charles-François du Périer Dumouriez (, 26 January 1739 – 14 March 1823) was a French general during the French Revolutionary Wars. He shared the victory at Valmy with General François Christophe Kellermann, but later deserted the Revo ...

managed to achieve a surprise victory over the Imperial command under the Duke of Saxe-Teschen and Clerfayt at the Battle of Jemappes. By the end of 1792, Dumouriez had marched largely unopposed across most of the Austrian Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, an area that roughly corresponds to present-day Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

. As the Austrians retreated, Dumouriez saw an opportunity with the Patriot exiles to overthrow the weak Dutch Republic by making a bold move north. A second French Division under Francisco de Miranda

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (28 March 1750 – 14 July 1816), commonly known as Francisco de Miranda (), was a Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary. Although his own plans for the independence of the Spani ...

manoeuvred against the Austrians and Hanoverians in eastern Belgium.

The French government issued a declaration on 16 November to end the and reopen the river for navigation after 200 years, as well as asserting the right of the French armies to pursue Austrian troops into neutral territory. Another decree on 19 November stated that the French Republic would support revolutionaries abroad. The British government regarded these statements and initial incursions into Dutch territory as violating the Netherlands' sovereignty and neutrality, and began preparing for war. Meanwhile, William V had joined the anti-French coalition, leading French forces to justify an invasion of Staats-Brabant. In December 1792, Miranda conquered Roermond

Roermond (; li, Remunj or ) is a city, municipality, and diocese in the Limburg province of the Netherlands. Roermond is a historically important town on the lower Roer on the east bank of the river Meuse. It received town rights in 1231. Roer ...

.

1793 campaign

Dumouriez's invasion of the Dutch Republic

Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

on 21 January 1793 stoked more fears amongst the other European monarchs that they would be next. France formally declared war on Britain and the Netherlands on 1 February 1793, and soon afterwards against Spain as well. Throughout 1793, the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, and Tuscany declared war on France. Allied armies mobilised along all of the French frontiers, the largest and most important in the Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

Franco-Belgian border region. British Prime Minister Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

pledged to finance the formation of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that suc ...

.

In the Low Countries, the Allies' immediate aim was to eject the French from the Dutch Republic (modern The Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

) and the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

), then march on Paris to end the chaotic and bloody French version of republican government. Austria and Prussia broadly supported this aim, but both were short of money. Britain agreed to invest a million pounds to finance a large Austrian army in the field plus a smaller Hanoverian corps, and dispatched an expeditionary force that eventually grew to approximately 20,000 British troops under the command of the king's younger son, the Duke of York. Initially, just 1,500 troops landed with York in February 1793.

On 16 February 1793, Dumouriez's republican Armée du Nord

The Army of the North or Armée du Nord is a name given to several historical units of the French Army. The first was one of the French Revolutionary Armies that fought with distinction against the First Coalition from 1792 to 1795. Others existe ...

advanced from Antwerp and invaded Dutch Brabant Brabant is a traditional geographical region (or regions) in the Low Countries of Europe. It may refer to:

Place names in Europe

* London-Brabant Massif, a geological structure stretching from England to northern Germany

Belgium

* Province of Bra ...

. Dutch forces fell back to the line of the Meuse abandoning the fortress of Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

after a short siege, and the Stadtholder called on Britain for help. Within nine days an initial British guards brigade had been assembled and dispatched across the English Channel, landing at Hellevoetsluis

Hellevoetsluis () is a small city and municipality in the western Netherlands. It is located in Voorne-Putten, South Holland. The municipality covers an area of of which is water and it includes the population centres Nieuw-Helvoet, Nieuwenhoo ...

under the command of general Lake

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much large ...

and the Duke of York. Meanwhile, while Dumouriez moved north into Brabant, a separate army under Francisco de Miranda

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza (28 March 1750 – 14 July 1816), commonly known as Francisco de Miranda (), was a Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary. Although his own plans for the independence of the Spani ...

laid siege to Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

on 23 February. However the Austrians had been reinforced to 39,000 and, now commanded by Saxe-Coburg, crossed the Roer River

The Rur or Roer (german: Rur ; Dutch and li, Roer, , ; french: Rour) is a major river that flows through portions of Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. It is a right (eastern) tributary to the Meuse ( nl, links=no, Maas). About 90 perc ...

on 1 March and drove back the Republican French near Aldenhoven

Aldenhoven () is a municipality in the district of Düren in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located approximately 5 km south-west of Jülich, 5 km north of Eschweiler and 20 km north-east of Aachen.

Gallery ...

. The next day the Austrians took Aachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

before reaching Maastricht on the Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a t ...

and forcing Miranda to lift the siege.

In the northern part of this theatre, Coburg thwarted Dumouriez's ambitions with a series of victories that evicted the French from the Austrian Netherlands altogether. This successful offensive reached its climax when Dumouriez was defeated at the Battle of Neerwinden on 18 March, and again at Louvain on 21 March. Dumouriez defected to the Allies on 6 April and was replaced as head of the Armée du Nord by general Picot de Dampierre. France faced attacks on several fronts, and few expected the war to last very long. However, instead of capitalising on this advantage, the Allied advance became pedestrian. The large Coalition army on the Rhine under the Duke of Brunswick

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

was reluctant to advance due to hopes for a political settlement. The Coalition Army in Flanders had the opportunity to brush past Dampierre's demoralised army, but the Austrian staff was not fully aware of the degree of the French weakness and, while awaiting the arrival of reinforcements from Britain, Hanover and Prussia, turned instead to besiege fortresses along the French borders. The first objective was Condé-sur-l'Escaut

Condé-sur-l'Escaut (, literally ''Condé on the Escaut''; pcd, Condé-su-l'Escaut) is a commune of the Nord department in northern France.

It lies on the border with Belgium. The population as of 1999 was 10,527. Residents of the area are kno ...

, at the confluence of the Haine

The Haine (, ; ; ; pcd, Héne; wa, Hinne) is a river in southern Belgium ( Hainaut) and northern France ( Nord), right tributary of the river Scheldt. The Haine gave its name to the County of Hainaut, and the present province of Hainaut. Its ...

and Scheldt

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of Netherlands, the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corr ...

rivers.

Coalition spring offensive

At the beginning of April the Allied powers met in conference at Antwerp to agree their strategy against France. Coburg was a reluctant leader and had hoped to end the war through diplomacy with Dumouriez, he even issued a proclamation declaring he was the "ally of all friends of order, abjuring all projects of conquest in the Emperors name", which he was immediately forced to recant by his political masters. The British desired

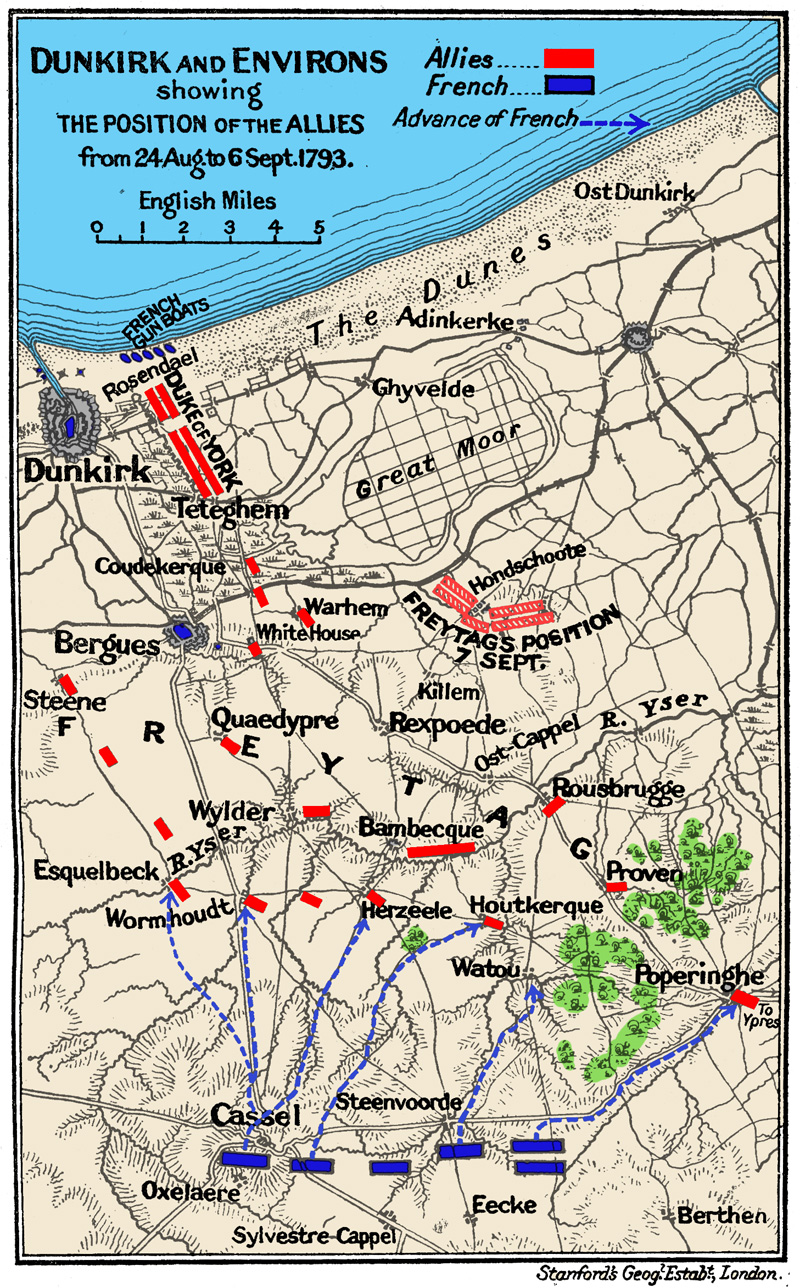

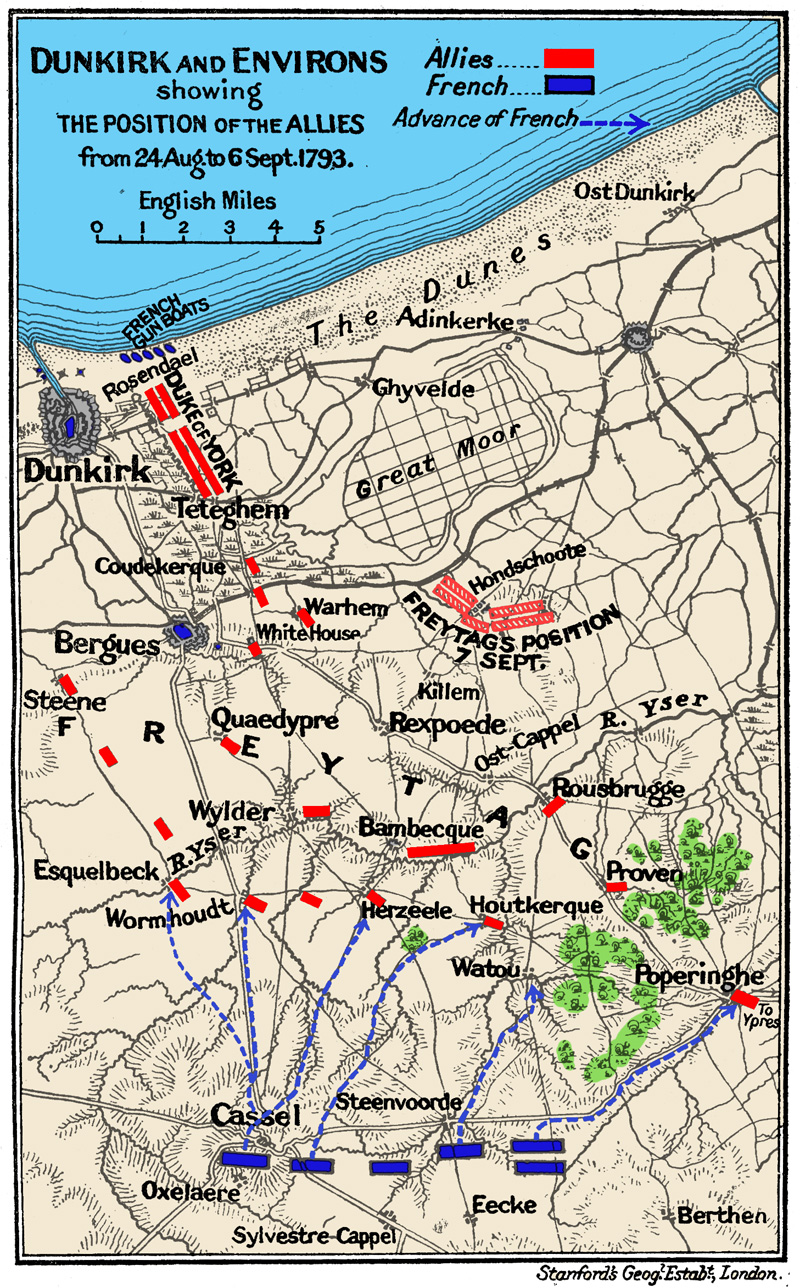

At the beginning of April the Allied powers met in conference at Antwerp to agree their strategy against France. Coburg was a reluctant leader and had hoped to end the war through diplomacy with Dumouriez, he even issued a proclamation declaring he was the "ally of all friends of order, abjuring all projects of conquest in the Emperors name", which he was immediately forced to recant by his political masters. The British desired Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.besieged Mainz, which held out from 14 April to 23 July 1793, and simultaneously mounted an offensive that swept through the

On 7/8 August the French, now under Charles Kilmaine were driven from Caesar's Camp north of

On 7/8 August the French, now under Charles Kilmaine were driven from Caesar's Camp north of

For 10 days a lull descended as both sides consolidated before Coburg launched attacks to regain the northern positions on 10 May.

For 10 days a lull descended as both sides consolidated before Coburg launched attacks to regain the northern positions on 10 May.

At this time, the French were reinforced by four divisions from the Army of the Moselle under Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, who had been ordered to reinforce the army on the Sambre while operating to the southeast against Johann Peter Beaulieu. Jourdan, who then took over command of the entire force, launched a fourth crossing and second siege of Charleroi. At the

At this time, the French were reinforced by four divisions from the Army of the Moselle under Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, who had been ordered to reinforce the army on the Sambre while operating to the southeast against Johann Peter Beaulieu. Jourdan, who then took over command of the entire force, launched a fourth crossing and second siege of Charleroi. At the

The battle of Fleurus would prove to be the decisive turning point. Historian

The Allied forces in Flanders were now divided into two distinct groups, the corps of the Duke of York, and the main Austrian and Dutch army under Coburg. While all forces were still nominally under Coburg's command, the two forces essentially functioned separately, with their own respective political objectives, and often without consideration for the other. Where Coburg's concern was to retreat eastward to protect the Rhine river and Germany from the French, York's objective was to retreat north to protect Holland.

Meanwhile, Pichegru's Army of the North had been menacing the Duke of York's forces on the Scheldt at Oudenaarde, but was ordered at the end of June to move to the coast and capture the Flemish ports of

The Allied forces in Flanders were now divided into two distinct groups, the corps of the Duke of York, and the main Austrian and Dutch army under Coburg. While all forces were still nominally under Coburg's command, the two forces essentially functioned separately, with their own respective political objectives, and often without consideration for the other. Where Coburg's concern was to retreat eastward to protect the Rhine river and Germany from the French, York's objective was to retreat north to protect Holland.

Meanwhile, Pichegru's Army of the North had been menacing the Duke of York's forces on the Scheldt at Oudenaarde, but was ordered at the end of June to move to the coast and capture the Flemish ports of

On 10 December, troops under

On 10 December, troops under

For the British and the Austrians the campaign proved disastrous. Austria had lost one of its territories, the

For the British and the Austrians the campaign proved disastrous. Austria had lost one of its territories, the

Rhineland

The Rhineland (german: Rheinland; french: Rhénanie; nl, Rijnland; ksh, Rhingland; Latinised name: ''Rhenania'') is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly its middle section.

Term

Historically, the Rhinelands ...

, mopping up small and disorganized elements of the French army. Meanwhile, in Flanders, Coburg began investing the French fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

s at Condé-sur-l'Escaut

Condé-sur-l'Escaut (, literally ''Condé on the Escaut''; pcd, Condé-su-l'Escaut) is a commune of the Nord department in northern France.

It lies on the border with Belgium. The population as of 1999 was 10,527. Residents of the area are kno ...

, now reinforced by the Anglo-Hanoverian corps of the Duke of York and Prussian contingent of Alexander von Knobelsdorff

Alexander Friedrich von Knobelsdorff (13 May 1723 in Cunow near Crossen – 10 December 1799 in Stendal) was a Prussian field marshal.

Biography

Knobelsdorff, originally a cavalry officer, had received awards in the Silesian Wars and was ...

. Facing the allies, though his men desperately needed rest and reorganisation, Dampierre was hampered and controlled by the representatives on mission

Representative may refer to:

Politics

*Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

*House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

*Legislator, someon ...

. On 19 April he attacked the Allies across a wide front at St. Amand but was beaten off. On 8 May the French attempted once more to relieve Condé, but, after a fierce combat at Raismes

Raismes () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. The flutist Gaston Blanquart (1877–1962) was born in Raismes.

Raismes is known for hosting the annual rock music festival Raismes Fest.

Population

Notable residents

* Pier ...

, in which Dampierre was mortally wounded, the attempt failed.

The arrival of York and Knobelsdorff raised Coburg's command to upwards of 90,000 men, which allowed Coburg to next move against Valenciennes

Valenciennes (, also , , ; nl, label=also Dutch, Valencijn; pcd, Valincyinnes or ; la, Valentianae) is a commune in the Nord department, Hauts-de-France, France.

It lies on the Scheldt () river. Although the city and region experienced a s ...

. On 23 May York's Anglo-Hanoverian forces saw their debut action at the Battle of Famars

The Battle of Famars was fought on 23 May 1793 during the Flanders Campaign of the War of the First Coalition. An Allied Austrian, Hanoverian, and British army under Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld defeated the French Army of the North le ...

. In the same region of the Pas-de-Calais, the French, now under François Joseph Drouot de Lamarche

François Joseph Drouot de Lamarche (14 July 1733 – 18 May 1814) briefly commanded a French army during the French Revolutionary Wars. He served in the French Royal Army as a cavalryman. In 1792 he was raised to the rank of general officer a ...

, were driven back in a combined operation which prepared the way for the siege of Valenciennes. Command of the Armée du Nord was given to Adam Custine, who had enjoyed success on the Rhine in 1792; however Custine needed time to re-organise the demoralised army and fell back to the stronghold of Caesar's Camp near Bohain

Bohain-en-Vermandois ( pcd, Bohain-in-Vérmindos) is a Communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Aisne in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

It is the place where the painter Henri Matisse grew up.

Etymology

Form ...

. Stalemate ensued as Custine felt unable to take the offensive and the allies focused on the sieges of Condé and Valenciennes. In July these both fell, Condé on 10 July, Valenciennes on 28 July. Custine was promptly recalled to Paris to answer for his tardiness, and guillotined.

Autumn campaign

On 7/8 August the French, now under Charles Kilmaine were driven from Caesar's Camp north of

On 7/8 August the French, now under Charles Kilmaine were driven from Caesar's Camp north of Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

. The following week in the Tourcoing

Tourcoing (; nl, Toerkonje ; vls, Terkoeje; pcd, Tourco) is a city in northern France on the Belgian border. It is designated municipally as a Communes of France, commune within the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), ...

sector Dutch troops under the Hereditary Prince of Orange attempted to repeat the success but were roughly handled by Jourdan Jourdan may refer to:

* Carolyn Jourdan, American author

*Claude Jourdan (1803–1873), French zoologist and paleontologist

* David W. Jourdan, businessman

*Jean-Baptiste Jourdan (1762–1833), French army commander

* Jourdan Bobbish (1994–2012), ...

at Lincelles until extricated by the British Guards brigade.

France was now at the mercy of the Coalition. The fall of Condé and Valenciennes had opened a gap in the frontier defences. The republican field armies were in disorder. However, instead of concentrating, the Allies now dispersed their forces. In the south Knobelsdorf's Prussian contingent departed to join the main Prussian army on the Rhine front, while in the north York was under orders from Secretary of State Dundas to lay siege to the French port of Dunkirk, which the British government planned to use as a military base and bargaining counter in any future peace negotiation. This led to conflict with Coburg, who needed the occupying forces to protect his flank by accompanying his thrust towards Cambrai. Lacking York's support the Austrians chose instead to besiege Le Quesnoy

Le Quesnoy (; pcd, L' Kénoé) is a commune and small town in the east of the Nord department of northern France. It was part of the historical province of French Hainaut. It had a keynote industry in shoemaking before the late 1940s, followed ...

, which was invested by Clerfayt on 19 August.

York's forces began the investment of Dunkirk, though they were ill-prepared for a protracted siege and had still not received any heavy siege artillery. The Armée du Nord, now under command of Jean Nicolas Houchard

Jean Nicolas Houchard (24 January 1739 – 17 November 1793) was a French General of the French Revolution and the French Revolutionary Wars.

Biography

Born at Forbach in Lorraine, Houchard began his military career at the age of sixteen in th ...

defeated York's exposed left flank under the Hanoverian general Freytag People with the surname Freytag (''Friday'' in German) include:

* Adam Freytag (1608–50), Polish mathematician and military engineer

* Arny Freytag, American photographer

* Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Freytag

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Freytag (19 S ...

at the Battle of Hondschoote

The Battle of Hondschoote took place during the Flanders Campaign of the Campaign of 1793 in the French Revolutionary Wars. It was fought during operations surrounding the siege of Dunkirk between 6 and 8 September 1793 at Hondschoote, Nord, ...

, forcing York to raise the siege and abandon his equipment. The Anglo-Hanoverians fell back in good order to Veurne

Veurne (; french: Furnes, italic=no, ) is a city and municipality in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the town of Veurne proper and the settlements of , , , , , Houtem, , , Wulveringem, and .

History

Origins up ...

(Furnes), where they were able to recover as there was no French pursuit. Houchard's plan had actually been to merely repulse the Duke of York so he could march south to relieve Le Quesnoy; on 13 September he defeated the Hereditary Prince at Menin (Menen

Menen (; french: Menin ; vls, Mêenn or ) is a city and municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of Menen proper and the towns of Lauwe and Rekkem. The city is situated on the French/Be ...

), capturing 40 guns and driving the Dutch towards Bruges and Ghent, but three days later his forces were routed in turn by Beaulieu at Courtrai

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

It is the capital and larges ...

.

Further south Coburg meanwhile had captured Le Quesnoy

Le Quesnoy (; pcd, L' Kénoé) is a commune and small town in the east of the Nord department of northern France. It was part of the historical province of French Hainaut. It had a keynote industry in shoemaking before the late 1940s, followed ...

on 11 September, enabling him to move forces north to assist York, and winning a signal victory over one of Houchard's Divisions at Avesnes-le-Sec

Avesnes-le-Sec () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Population

Heraldry

See also

* Chemin de fer du Cambrésis

*Communes of the Nord department

The following is a list of the 648 communes of the Nord department of ...

. As if these disasters were not enough for the French, news reached Paris that in Alsace the Duke of Brunswick had defeated the French at Pirmasens

Pirmasens (; pfl, Bärmesens (also ''Bermesens'' or ''Bärmasens'')) is an independent town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, near the border with France. It was famous for the manufacture of shoes. The surrounding rural district was called ''Lan ...

. The Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

s were stirred into a ferocity of panic. Laws were imposed that placed all lives and property at the disposal of the regime. For failing to follow up his victory at Hondschoote and the defeat at Menen, Houchard was accused of treason, arrested, and guillotined in Paris on 17 November.

At the end of September Coburg began investing Maubeuge

Maubeuge (; historical nl, Mabuse or nl, Malbode; pcd, Maubeuche) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

It is situated on both banks of the Sambre (here canalized), east of Valenciennes and about from the Belgian border ...

, though the allied forces were now stretched. The Duke of York was unable to offer much support as his command was greatly weakened, not only by the strain of the campaign, but also by Dundas in London, who began withdrawing troops to reassign to the West Indies. As a result, Houchard's replacement Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, 1st Count Jourdan (29 April 1762 – 23 November 1833), was a French military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was made a Marshal of the Empire by Emperor Napoleon I in ...

was able to concentrate his forces and narrowly defeat Coburg at the Battle of Wattignies

The Battle of Wattignies (15–16 October 1793) saw a French army commanded by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan attack a Coalition army directed by Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. After two days of combat Jourdan's troops compelled the Habsburg co ...

, forcing the Austrians to lift the siege of Maubeuge. The Convention then ordered a general offensive towards York's base at Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

. In mid October Vandamme Vandamme is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alexandre Vandamme (born 1962), Belgian businessman

* Dominique Vandamme (1770–1830), French military officer

* George Vandamme, Belgian wheelchair racer

* Jamaïque Vandamme (born ...

laid siege to Nieuport

Nieuport, later Nieuport-Delage, was a French aeroplane company that primarily built racing aircraft before World War I and fighter aircraft during World War I and between the wars.

History

Beginnings

Originally formed as Nieuport-Duplex in ...

, MacDonald took Wervicq and Dumonceau drove the Hanoverians from Menen, however the French were forced back in sharp rebuffs at Cysoing on 24 October and Marchiennes

Marchiennes () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

It was fictionally portrayed in Émile Zola's Germinal.

Heraldry

See also

*Communes of the Nord department

The following is a list of the 648 communes of the Nord dep ...

on 29 October, which effectively brought an end to the year's campaigning.

1794 campaign

Over the winter both sides re-organised. Reinforcements were transported from Britain in order to shore up the Coalition line. In the Austrian army Coburg'sChief of Staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

Prince Hohenlohe was replaced by Karl Mack von Leiberich

Karl Freiherr Mack von Leiberich (25 August 1752 – 22 December 1828) was an Austrian soldier. He is best remembered as the commander of the Austrian forces that capitulated to Napoleon's ''Grande Armée'' in the Battle of Ulm in 1805.

Early ...

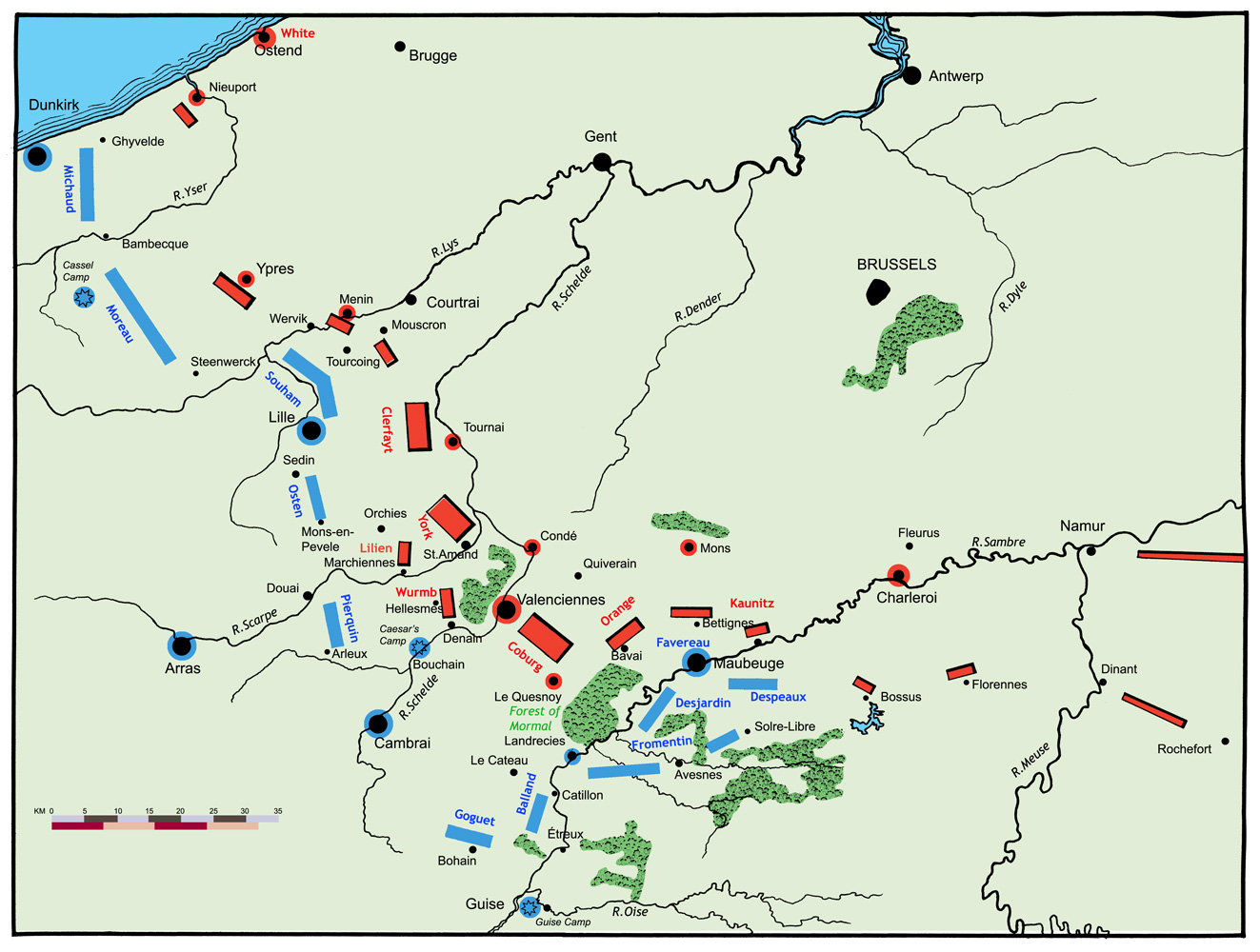

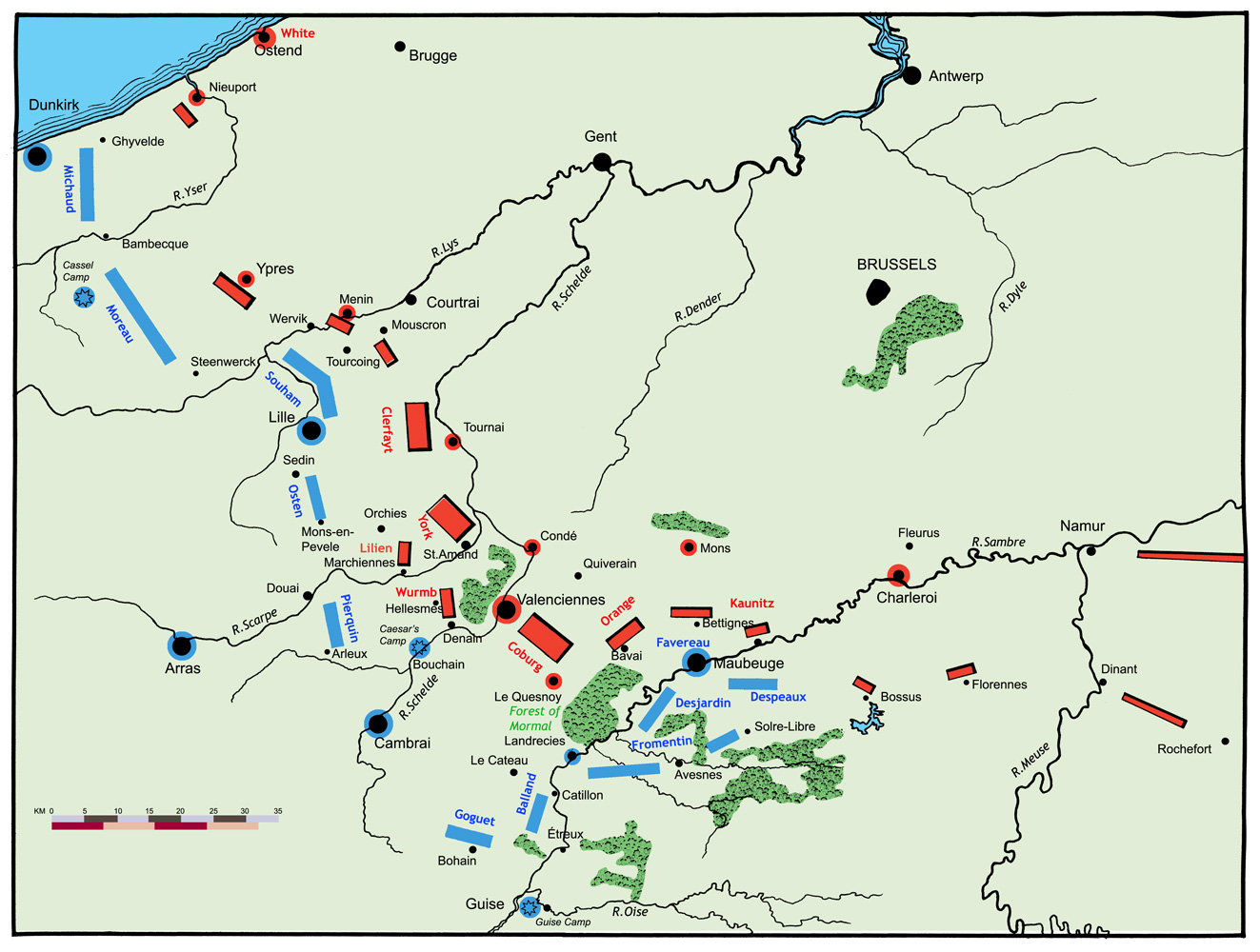

. At the beginning of 1794 the allied field army numbered somewhat over 100,000 troops, the bulk of the army in positions between Tournai

Tournai or Tournay ( ; ; nl, Doornik ; pcd, Tornai; wa, Tornè ; la, Tornacum) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies southwest of Brussels on the river Scheldt. Tournai is part of Euromet ...

and Bettignies

Bettignies () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territo ...

, with both flanks further extended with small outposts and cordons to the Meuse on the left and the Channel coast on the right. Facing them the Armée du Nord was now under the command of Jean-Charles Pichegru

Jean-Charles Pichegru (, 16 February 1761 – 5 April 1804) was a French general of the Revolutionary Wars. Under his command, French troops overran Belgium and the Netherlands before fighting on the Rhine front. His royalist positions led to h ...

, and had been greatly reinforced by conscripts as the result of the ''Levée en masse

''Levée en masse'' ( or, in English, "mass levy") is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period followi ...

'', giving the combined strength of the Armies of the North and Ardennes (excluding garrisons) as 200,000, nearly two to one of Coburg's force.

Siege of Landrecies

At the beginning of April 1794, Austrian troops were greatly encouraged when the Emperor Francis II joined Coburg at Allied headquarters. The first action of the campaign was a French advance from Le Cateau on 25 March, which was beaten off by Clerfayt after a sharp fight. Two weeks later the Allies began their advance with a series of covered marches and small actions to facilitate the investment of the fortress ofLandrecies

Landrecies (; nl, Landeschie) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

History

In 1543, Landrecies was besieged by English and Imperial forces, who were repulsed by the French defenders. In 1794, it was besieged by Dutch forces, ...

. York advanced from Saint-Amand towards Le Cateau, Coburg led the centre column from Valenciennes and Le Quesnoy, and to his left the Hereditary Prince led the besieging corps from Bavay

Bavay () is a commune in the Nord department in the Hauts-de-France region of northern France. The town was the seat of the former canton of Bavay.

The inhabitants of the commune are known as ''Bavaisiens'' or ''Bavaisiennes''

Geography

Bava ...

through the Forest of Mormal towards Landrecies. On 17 April York drove Goguet from Vaux and Prémont, while the Austrian forces advanced in the direction of Wassigny

Wassigny () is a commune in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Population

See also

* Communes of the Aisne department

The following is a list of the 799 communes in the French department of Aisne.

The commun ...

against Balland. The Hereditary Prince then began the Siege of Landrecies

The siege of Landrecies (1543) took place during the Italian War of 1542–46. Landrecies was besieged by Imperial and English forces under the command of Ferrante Gonzaga

Ferrante I Gonzaga (also Ferdinando I Gonzaga; 28 January 1507 – 1 ...

, while the Allied army covered the operation in a semi-circle. On the Left at the eastern end of the line lay the commands of Alvinczi and Kinsky

The House of Kinsky (formerly Vchynští, sg. ''Vchynský'' in Czech; later (in modern Czech) Kinští, sg. ''Kinský''; german: Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau) is a prominent Czech noble family originating from the Kingdom of Bohemia. During the ...

, stretching from Maroilles four miles east of Landrecies, south to Prisches

Prisches () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

History

Catharina Trico, born at Prisches (then part of the Spanish Netherlands) emigrated in the early 17th Century to Amsterdam. On January 13, 1624, she - 18 years old at t ...

, then south-west to the line of the Sambre

The Sambre (; nl, Samber, ) is a river in northern France and in Wallonia, Belgium. It is a left-bank tributary of the Meuse, which it joins in the Wallonian capital Namur.

The source of the Sambre is near Le Nouvion-en-Thiérache, in the Aisne ...

river. On the western bank of the river the line ran west from Catillon

Catillon-sur-Sambre (, literally ''Catillon on Sambre'') is a commune of the Nord department in northern France.

Heraldry

See also

*Communes of the Nord department

The following is a list of the 648 communes of the Nord department of the ...

towards Le Cateau and Cambrai. The right of the Allied line was under the Duke of York and ended near Le Cateau. A line of outposts then ran north-west along the line of the Selle river.

The French plan was to attack both flanks of the allies, while sending relief columns towards Landrecies. On 24 April a small force of British and Austrian cavalry drove back just such a force under Chapuis at Villers-en-Cauchies. Two days later Pichegru launched a three-pronged attempt to relieve Landrecies. Two of the columns in the east were repulsed by the forces of Kinsky

The House of Kinsky (formerly Vchynští, sg. ''Vchynský'' in Czech; later (in modern Czech) Kinští, sg. ''Kinský''; german: Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau) is a prominent Czech noble family originating from the Kingdom of Bohemia. During the ...

, Alvinczi and the young Archduke Charles

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

, while Chapuis's third column advancing from Cambrai was all but destroyed by York at Beaumont/Coteau/Troisvilles on 26 April.

French May counter-offensive

Landrecies fell on 30 April 1794 and Coburg turned his attention toMaubeuge

Maubeuge (; historical nl, Mabuse or nl, Malbode; pcd, Maubeuche) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

It is situated on both banks of the Sambre (here canalized), east of Valenciennes and about from the Belgian border ...

, the last remaining obstacle to an advance on the French interior. But on the same day Pichegru began his overdue northern counter-offensive, defeating Clerfayt at the Battle of Mouscron

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

and retaking Courtrai (Kortrijk

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian City status in Belgium, city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Regio ...

) and Menen.

For 10 days a lull descended as both sides consolidated before Coburg launched attacks to regain the northern positions on 10 May.

For 10 days a lull descended as both sides consolidated before Coburg launched attacks to regain the northern positions on 10 May. Jacques Philippe Bonnaud

Jacques Philippe Bonnaud or Bonneau (11 September 1757 – 30 March 1797) commanded a French combat division in a number of actions during the French Revolutionary Wars. He enlisted in the French Royal Army as cavalryman in 1776 and was a non-com ...

's French column was defeated by York at the Battle of Willems, but Clerfayt failed to recapture Courtrai and was again driven back in the Battle of Courtrai.

The Coalition forces planned to stem Pichegru's advance with a broad attack involving several isolated columns in a scheme devised by Mack. At the Battle of Tourcoing

The Battle of Tourcoing (17–18 May 1794) saw a Republican French army directed by General of Division Joseph Souham defend against an attack by a Coalition army led by Emperor Francis II and Austrian Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. T ...

on 17–18 May this effort became a logistical disaster as communications broke down and columns were delayed. Only a third of the allied force came into action, and were only extricated after the loss of 3,000 men. Pichegru being absent on the Sambre, French command at Tourcoing had devolved onto the shoulders of Joseph Souham

Joseph, comte Souham (30 April 1760 – 28 April 1837) was a French general who fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was born at Lubersac and died at Versailles. After long service in the French Royal Army, he was e ...

. On his return to the front Pichegru renewed the offensive to press his advantage but despite repeated attacks was held off at the Battle of Tournay on 22 May.

Meanwhile, the eastern prong of Pichegru's offensive was taking place on the Sambre river, where divisions of the right wing of Pichegru's Army of the North under Jacques Desjardin and the Army of the Ardennes under Louis Charbonnier attacked across the river to try and establish a foothold on the northern bank. Their objective was the capture of Mons, which would cut the lines of supply and communication from the main Allied base at Brussels to Coburg's centre around Landrecies and Le Quesnoy.

The first French crossing was turned back at the battle of Grand-Reng

The Battle of Grand-Reng or Battle of Rouvroi Smith provided the battle's name. (13 May 1794) saw a Republican French army jointly commanded by Louis Charbonnier and Jacques Desjardin attempt to advance across the Sambre River against a combi ...

on 13 May, where a fatally divided high command led to the failure of Desjardin's frontal attack on Allied commander Prince Kaunitz while Charbonnier stood by and ignored the battle, leaving Desjardin vulnerable to an Allied counterattack. A second attempt at consolidating a foothold on the north bank was defeated at the battle of Erquelinnes

The Battle of Erquelinnes or Battle of Péchant This source gave the two names of the battle. (24 May 1794) was part of the Flanders Campaign during the War of the First Coalition, and saw a Republican French army jointly led by Jacques Desja ...

on 24 May as the Allies surprised the French by attacking out of early morning fog.

Although the allied front remained intact, subsequently the Austrian commitment to the war became increasingly weakened. The Prussians were already on the point of pulling out of the war due to perceived Austrian duplicity in Bavaria. The Emperor was strongly influenced by Foreign Minister Baron Johann von Thugut, and for Thugut political considerations always overrode military plans. In May 1794 his fixation was with profiting from the Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Polish ...

, and troops and generals began to be stripped from Coburg's command. Mack resigned as Chief-of-Staff in disgust on 23 May and was replaced by Prince Christian August von Waldeck-Pyrmont, a supporter of Thugut. In a Council of War

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

on 24 May Emperor Francis II

Francis II (german: Franz II.; 12 February 1768 – 2 March 1835) was the last Holy Roman Emperor (from 1792 to 1806) and the founder and Emperor of the Austrian Empire, from 1804 to 1835. He assumed the title of Emperor of Austria in response ...

called for a vote on withdrawal, then left for Vienna. Only the Duke of York dissented with the withdrawal.

The decision to retreat was taken despite victories on southern flank such as Grand-Reng, Erquelinnes, and Wichard Joachim Heinrich von Möllendorf

Wichard Joachim Heinrich von Möllendorf (7 January 1724 – 28 January 1816) was a Generalfeldmarschall of the Kingdom of Prussia.

Life and career

Möllendorf was born in Lindenberg (Prignitz), now a part of Wittenberge, in the Margraviate of B ...

's victory at the Battle of Kaiserslautern

The Battle of Kaiserslautern (28–30 November 1793) saw a Coalition army under Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel oppose a Republican French army led by Lazare Hoche. Three days of conflict resulted in a victory by th ...

after his Prussians surprised the French on 24 May. With the northern flank temporarily stabilised Coburg moved forces south to support Kaunitz, who promptly resigned after being replaced by the Hereditary Prince. Pichegru then took advantage of the weakening of the Allied northern sector to return to the offensive and initiate the Siege of Ypres on 1 June. A series of supinely ineffective counter-attacks by Clerfayt through the first half of June were all beaten off by Souham.